The Correspondences:

Richard and Alan Bishop

In the pantheon of modern music, the ensemble, the phenomenon, known as Sun City Girls (Richard and Alan Bishop, and Charles Gocher) is unique in the true sense of word, in that something is either unique or it is not. Originally from Phoenix, the group gradually relocated to Seattle in the late 1980's-early 1990's. Like Giant Sand or Meat Puppets, who also emerged from Arizona in the early 1980's—indeed, like countless Rock bands in the post-Hardcore milieu—Sun City Girls were comfortable within the Rock tradition; but they were not confined by it, bringing in, on one hand, aspects of Jazz and Improvised music, on the other numerous methods and sounds from North Africa, the Near East, India, Asia, and the Americas—all the while avoiding the perils of ironic appropriation. After all, the techniques Sun City Girls use, as instrumentalists, writers, and recording artists, often produce results that are merely similar to what one hears in various traditional musics, Jazz, and even electroacoustic music and modern literature. Richard Bishop teaches himself to play guitar, and in the process draws upon childhood experiences with his Lebanese grandfather, who played the oud and other instruments, and had friends and family over for all-night sessions of Arabic music. His brother Alan, both with Sun City Girls and alone (for releases on the Sublime Frequencies label) creates "radio" works: collages whose constituent parts, combed from sources collected over a span of decades, are multifarious in such a variety of ways (place, purpose, recording method) that they rival in scale and scope the major works of legendary Academic Electroacoustic composers. Charles tells tales of absurdist fantasy, excitedly traveling through time and space, and often possessed by scatological humor; the listener cannot help but think of the rebellion waged by the Beats, the Surrealists, and others (Georges Bataille, Henry Miller, Antonin Artaud) against the internal barriers writers imposed on themselves for the sake of decorum, tradition, and "realism."

Further inverted contradictions abound. They found support from Phoenix's "skate Punk" scene, as one of a handful of adventurous acts recording for Placebo Records and partaking in their first national tour in 1984 supporting Jodie Foster's Army. While they challenged Hardcore orthodoxy during such endeavors, and got the predictable hostile response, they claimed to relish the challenge. Fittingly, while many of their peers aimed to infiltrate mass consciousness, visions of cultural revolution dancing about in their heads, Sun City Girls pioneered the practice of self-released recordings. Early on, most of these were cassettes, making them a crucial part of the "cassette underground" of the 1980's-early 1990's. Nonetheless, through the Majora Records label, the group released several seminal albums, including Torch of the Mystics, Dawn of the Devi, Bright Surroundings Dark Beginnings, and Live From Planet Boomerang, establishing for many their esteemed place as recording artists, if the cassettes hadn't already. In Seattle, the band reaffirmed the self-published (D. I. Y.) route, setting up Abduction Records to release most of their records, as well as on occasion those of other artists. As a live act, while one could argue that Sun City Girls were ultimately just a Rock trio, albeit one that often engaged in the kind of collective improvisation that leaves the listener certain the participants possess a nearly-telepathic rapport with each other, they were also capable of redefining the very notion of the nightclub gig, sometimes preferring to enact one of their Cloaven Theatre works, other times abandoning their guitars and drums and turning instead to their large collection of instruments from around the world. Or, perhaps, they did all these things for the same show.

With their later works, Sun City Girls again countered common expectations regarding Rock bands. Though many Rock artists in their later years have created works as formidable as their best early records, rarely do they do so in a fundamental way, taking little for granted, as Sun City Girls did with 330,003 Crossdressers From Beyond the Rig Veda and Dante's Disneyland Inferno, double C. D.s both released in 1996, and with the Carnival Folklore Resurrection series, begun in 2000. And yet the band also began to take stock in what they had accomplished, digging through their archives, examples of which constitute the sprawling triple C.D Box of Chameleons (1997) and parts of the aforementioned "radio" works. The band's concert tours in 2002 and 2004, combined with renewed interest in the group as a new generation of listeners came aboard, together served as an excellent culmination of their careers to date. While Alan's and Richard's solo albums have of late received more attention, the massive Sun City Girls oeuvre remains, to beguile and entrance listeners for years to come: three distinct artists, each of whom in and of themselves could have become a cottage industry, with many minions eager to do the brunt work, instead came together in the ecstatic frenzy of the Punk era to forge a common course, understanding that what defines an artist's path is precisely its circuitous nature, its countless apparent detours.

In February, 2007, Charles Gocher passed away after several years of struggling with cancer, thus bringing Sun City Girls to an end. Please visit the memorial site. Also visit the official sites for Sun City Girls, Sir Richard Bishop, and the Sublime Frequencies label.

The exchange of comments and questions with Richard Bishop took place from March to November, 2011. The photographs featured on this page were all taken by Richard in October, 2007, except as indicated. Also read the companion Alan Bishop correspondence on the next page.

--

J. Kaw

You've spoken of your appreciation of the Hindu deity Kali; and she is the subject of a story written by Charles Gocher included in the liner notes for the C.D version of Torch of the Mystics, one of her several appearances in the Sun City Girls oeuvre (not to mention the title of the first Sir Richard Bishop album, Salvador Kali). Kali of course holds a place of great significance in the rituals, texts, and visual art of Tantric Hinduism, especially what is called "left-handed" Tantrism. With its emphasis on rituals seeking to overcome or unite dualities, especially male-female, the body comes to the forefront, and in turn sexuality. With regard not only to Hinduism but Buddhism and ecumenical traditions as well, Tantrism involves the purposeful transgression of social mores and taboos, partaking in the forbidden. For their part, Sun City Girls violated all sorts of cultural and social boundaries, especially in vocal and literary form. The lyrics, stories, etc., are more likely to shock or annoy the listener, rendering the band's products as too gauche and awkward for casual listeners. Not only with regard to profane and scatological content, but in refusing to take the "high road" in political matters—accepting a certain lack of tact and rationality—we see a broader social import of Tantric notions of transgression as manifested in Sun City Girls music. Yet, of course, the listener doesn't exactly get the impression that you, Alan, and Charles accepted the validity of such boundaries to begin with, while in contrast the embrace of the impure and the debased in many Tantric traditions ultimately serves to affirm the higher status of ascetic methods and ideals of purity. As such, a different understanding of Kali becomes more appropriate. David Kinsley, author of the seminal The Sword and the Flute [1975], in his later book Hindu Goddesses [1986] has suggested his own dualism, between the devotee of Kali and the adept, or "Tantric hero." The former's relationship to Kali he describes, not pejoratively, as comparable to that of a child towards his mother. The Tantric hero, on other hand, conforms more to common view of the follower of Kali, excitedly traversing societal and spiritual norms, attempting to share or experience a sampling of her power. For the devotee on the other hand, what's forbidden is, above all else, the truth, especially the need for reconciliation with death and the way in which death often comes unexpectedly, upsetting neat conceptions of the order of dharma. You suggest a similar perspective in your and Alan's interview with Ian Svenonius on his television program Soft Focus, saying of Kali, "she's nothing bad, nothing evil, nothing dark," "an energy that has somehow [...] made contact," and also suggesting to the audience that personal experience with the beauty and power of Kali-centric temples and rituals, such as animal sacrifice, is necessary.

Wat mural, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2009

To get back to our contemporary context, in this era of economic stagnation, "ironic" reactionary cultural preferences, and renewed anti-intellectual demagoguery, many of the Americans who have studied and practiced Hindu, Buddhist, and other Indian and Eastern religions/ philosophies, and subsequently brought them Westward (or, if you like, eastward across the Pacific), have come—to put it nicely—from the upper classes, or at least have represented the sheltered interests of academia. Whereas, in the post-Second World War era, and then especially amid the social upheavals of the 1960s and early 1970s, interest in such matters grew enormously and began to permeate mass culture. Sun City Girls, in this respect and in other ways, fit in better with the era preceding its own formation.

Other potential connections to your work and that of Sun City Girls.... First, the perspective on politics you mentioned in Soft Focus interview, wherein "laws, politicians, government" are figuratively placed underneath one's feet, to be crushed if need be; that such matters should not effect our daily lives or command our respect. Yet you note your lack of confidence in the ability of most humans to achieve such state of mind, at least not without the impetus of extraordinary disorder. This kind of positive misanthropy, hatred and anger directed toward fruitful pursuits, not merely causing further stupidity similar to that which justly caused the misanthropy in the first place, is definitely fostered by metaphysical, non-humanist understandings of reality. In other words, acceptance that other humans—social gatherings, networks, institutions—offer little more than further enslavement. Second, as Alan writes in his appreciation of Charles written for Perfect Sound Forever, for artists "respect or recognition comes with a price. A price of judgment and convenient categorization or being boxed in a culturally organized place for reference and historical context." This recognition of a basic lack of respect for art in contemporary civilization might seem too obvious or hackneyed, but if we bring in conceptualizations of the social status of artists further afield, more foreign or "exotic" to our own, such as the artist as shaman or priest, we might see with greater clarity the current denigrated position of the artist.

Richard Bishop

I can't imagine how Sun City Girls would have been looked upon if we were active in the 1960s or early '70s. Hell, I would have probably been an acid casualty. We began at exactly the right time. The hippy dippy stuff was long gone, the '70s guitar Rock I had been into was dead in the water, Punk was still happening but remained as one-dimensional as it was when it first started, plus much of the new wave music and eventually the '80s hair bands brought artistic stupidity to a new level. There wasn't a God Damned challenging thing to grab onto. We were our own perfect solution.

There was no reason to acknowledge any boundaries. In fact, regardless of one's artistic or attainment goals it's easier to comprehend the basic precepts of Kali and Sun City Girls if one recognizes that in reality no such boundaries exist—no dualities, social mores, taboos, or even rules. You just get that out of the way immediately. I don't believe in the old adage that one must know and understand the rules before one can break them. That's faulty logic. If the subject matter of Sun City Girls's lyrical or spoken word content (or even the music itself) was awkward or shocking to some people, I don't see anything wrong with that at all. They should feel good about it. I would love to be shocked by any musical entity; I've been waiting for years. C'mon people, step it up. We knew what we were doing and we were aware that it wasn't going to sit well with everybody, but we didn't care about that. All we cared about was our ability to do, say, think, and play whatever we wanted. We weren't responsible for, nor did we care about, anybody's feelings. Everything was on our terms; once you commit to doing things for yourself, you quickly realize how ridiculous it is to rely on, or worry about, others. I personally was never concerned about being respected or having our art or music be recognized by anybody. In fact, all three of us were pretty confident from the start that Sun City Girls would never be officially recognized or analyzed in any musical history books and to this day, internet aside, that pretty much holds true. That's a great honor.

People used to say we were sun-damaged. I like to think that we were just solar-powered. We were able to generate, harness, and project our own reality, our own unique energy. Those that know Kali know that she is Shakti—primordial energy that can take any multitude of forms. She is unlimited in this respect. One must constantly peel away the layers in order to see things in all their proper (or improper) contexts. One could draw a similar parallel to the wonderful musical stylings of Sun City Girls. And yes, many of the earliest writers on Kali came from the upper classes. Most of the earliest English-language writings concerning Kali, and the whole Hindu pantheon, were derogatory hit pieces (Sun City Girls had their share of those as well) depicting the savagery of the unenlightened natives, totally at odds with the unquestioned view of Christian superiority at that time. But they at least brought the subject matter into the light. The recent books by Kinsley (and others) do a great job of introducing her many forms and attributes but it is necessary to go beyond Western analysis. One should consult the original Hindu textual sources where all forms of her worship and the magical properties attained from that worship, as well as her entire history and mythology, are expounded in great detail. One of the basic texts is the Karpuradi-stotra (Hymn to Kali), which consists of twenty-two short verses (one for each syllable of her great mantra); here, much of her worship is described, and the differences between the Vira (Tantric Hero) and the Pasu (the animal-man) are also addressed. This is required reading and the best place to start. The Kalika Purana takes things much further and dissects the worship of Durga, Kali, and Kamakhya (Mahamaya). The amount of detail in this massive text is overwhelming and downright confusing at times but it is important to mine the information, meditate on it, and interpret things personally, based on instinct and feeling, relying on nobody else.

Though books will only get you so far, they do provide the necessary foundation to continue moving forward. One then needs to voluntarily enter Kali's universe, her surroundings, her iconography. Tradition tells us that in order to really experience the true nature of Kali, or any Tantric deity for that matter, you must align yourself with a guru who can lead you in the right direction, transmit the mantras—the current, the clan fluid, or whatever you want to call it—depending on which school or path you are following. For me, however, it is the Goddess herself who is Guru. Why be a follower when one can dial direct? I found that visiting her temples, and seeing, experiencing, and "feeling" many of her rituals firsthand, reinforced my desire to continue—in fact, it cranked things up a few notches. You then get to the point where there is no turning back. So if you find yourself in India, make a visit (or several) to one of the many Kali or Tara temples, and just let the fun begin. And if you're feeling adventurous go back at midnight (no moon allowed) and enter the cremation ground—it's usually out back, follow the scent of burning flesh. Then all you have to do is sit down, close your eyes and shut up. See how long you last. Afterward, I'll totally understand if you don't want to talk about it!

Kali priestesses - Guwahati, Assam, India

Speaking of foul stenches, there is no "high road" in politics—it's just one big cul de sac of crap. The Soft Focus segment we did for Vice T. V. was quite the drunken affair. I thought it was quite hilarious though many in the audience weren't laughing. Before the segment was taped we were back stage talking with host Ian Svenonius and Jesse Pearson (from Vice); they both told stories about how they had had previous visits from the Secret Service for one reason or another, which set the tone for the evening. We already had planned to have Mark Gergis dress up as a terrorist, complete with exploding briefcase, and sit behind us for the entire taping. We introduced him as Carlos, our bodyguard. Those in the audience who were familiar with Sun City Girls probably knew this wasn't going to be a happy little interview. Alan and I didn't know which direction it would take but it was agreed that we would "take it out on the Dixie." Obama had been elected President just a couple of days before. A lot of people at that time (including most of the studio audience) were still euphoric about Obama's victory—even Oprah's tears hadn't dried yet. It was as if he was the new messiah and he was going to fix everything with his "Yes we can can, why can't we if we wanna, yes we can can" Pointer Sisters shtick. It reassured everybody that their vote actually does count, which is a laugh because Obama had been groomed and handpicked to be President at a Bilderberger meeting a few years prior. You don't just come out of nowhere and assume the top job. By the way, how's that hope-and-change shit going? Having a good time, are we? Anyway, since Obama was the hot topic, I went off on how he was already the perfect candidate for a presidential assassination. You see, we hadn't had a good presidential assassination (or even a decent attempt) in a while and since he was almost instantly achieving that popular Kennedy-like status, I stressed that his death could affect millions of people the world over and could be used quite easily to further any number of agendas desired by the ruling elite. "I know we can make it work, I know we can make it if we try, yes we can, I know we can can." Well, it didn't get the attention of the Secret Service but the reaction by many of the audience members—the initial shock and horror on their faces when hearing such things—was priceless. The interview didn't gain us any popularity but that was nothing new. Jello Biafra was to be interviewed live right after us. When we were through, he said, "How can I follow something like that? That was the most Punk Rock thing I've ever seen." Methinks he perhaps needs to get out more—that was nothing! But once he took the stage, the audience members breathed a sigh of relief and Jello told his funny little stories and anecdotes and it felt safe again and everybody laughed. And there were rainbows and unicorns and fairy dust and then everybody went back to sleep. God Fucking Bless America.

My point about laws, politicians, and government being made small enough to be placed beneath one's feet to be crushed when necessary is very simple. That is how politicians view the common people, so what's the problem? 99.9% of all politicians don't give a shit about you or me except in relation to extracting as much money from us as is possible and making us all debt slaves. So fuck them. Everybody should ask themselves one question: "Do I need to be governed?" Well do ya, punk? We're all visitors here for a very short time. These fuckers and their money-junkie friends are a distraction, they're in the way. Rise above them; make them your playthings instead of it being the other way around. Put them behind you or below you (crush them), or just forget about them altogether. Look at the world right now. It's totally fucked up. When I was in New York recently I went down to the Occupy Wall Street thing just to check it out. I did see a few people who were well organized and quite informed about the financial disaster that this country is currently faced with. Unfortunately, the rest of the people there seemed to think they were at Burning Man. Enough with the drum circles and the celebratory atmosphere. It's not a fucking party and there is nothing to celebrate. The whole movement does have the potential to raise awareness, but there are so many different issues and agendas and organizations that have entered the fray, it becomes difficult to stay focused on anything long enough to have the ability to change policy or the system. Too many long-established divisions remain. As long as people keep thinking in terms such as Democrat or Republican, Liberal or Conservative, Black or White or whatever color, Gay or Straight, or any other divided sub-group, there will be no progress in any occupation or protest movement. Everybody will always be blaming the other side instead of focusing their energies on those at the top of the pyramid. As long as any divisions remain the power structures at the top will continue to laugh, sip their champagne, and proceed to stamp their boot-print into the skulls of a populace that is not capable of uniting. Divide and Conquer—how many times does one need to hear that phrase before realizing it is the one simple tool that keeps people from making any progress against the real villains? It's worked for thousands of years and it will continue to do so until people wake the fuck up and realize their folly. But if the focus can stay on getting rid of the Federal Reserve, the private central bankers (worldwide), and the other corporate criminals (the money junkies) responsible for the mortgage-backed securities fraud that started this whole mess—then maybe something will change. Iceland did it. In the meantime get the fuck out of debt, people, and start exchanging some of those soon-to-be worthless pieces of green paper (with the dead presidents on 'em) for supplies and goods that will help you survive the madness that is coming (may I recommend canned goods and firearms?). Get as far away from the current system as possible. Remove yourself from the game. Because right now that's all it is—a game—and you can't win. But don't listen to me—I'm completely insane, can't you tell? Speaking of insanity, here's a little financial tip for you: start hoarding nickels—that's right, nickels!

Disheveled Richard, Guwahati, Assam, India

J. Kaw

You talked in the Popwatch/ Perfect Sound Forever interview in 1999 about your grandfather, who lived not far from your parents' place in Saginaw, Michigan, being a master oud player and leader of informal music-making sessions among the Lebanese community there. But in the same interview you describe teaching yourself to play guitar and piano, suggesting that you did not learn directly from your grandfather or other skilled musicians. More recently, the acclaimed Egyptian guitarist and composer, Omar Khorshid, inspired much of the 2009 Sir Richard Bishop album, The Freak of Araby, suggesting again the power of indirect, impersonal influences. Indeed, that album might at first have sounded to many listeners as an exception to your rule: bringing a variety of guitar styles—Surf, Hard Rock, Gypsy, Arabic—together in a confounding but brilliant mishmash, as heard on most of your solo work as well as guitar-oriented Sun City Girls albums like Libyan Dream and Wah. Alas, the album is probably not, strictly speaking, Arabic music, or at least obviously not meeting any standard of an unadulterated ethnic or national cultural tradition. Meanwhile, I'd like to inquire about influences on your guitar playing less immediately apparent: Blues or Country and Western? Flamenco and other Hispanic and European genres? Or the West African styles featured recently on Sublime Frequencies?

Richard Bishop

I don't know what is apparent or less apparent. The guitarists who have influenced my playing have changed considerably over the years. Most of the old ones either died out or hit a wall and new ones are just plain hard to find. I've stopped looking. I'm kind of sick of guitar players. Aren't you? Back when my grandfather and his friends were playing their music in the basement in Saginaw I was still quite young. I had no intention of becoming a musician yet. I was exposed to a lot of music when I was little—it's just not always clear what may have inspired me later on, but it is worth exploring. Like most people my age it started with music from cartoons—Carl Stalling and Hoyt Curtin mostly. Curtin's opening and closing theme from the original Jonny Quest cartoon (1964) was my favorite piece of music when I was a kid. And almost every Saturday on T. V. they would show one of the films with the Ray Harryhausen monsters with those great Bernard Herrmann scores. And then there was the creepy music from Dark Shadows, which I watched religiously as a kid. A lot of these sounds inspired me over the years. Our parents knew that Alan and I had some interest in music but they weren't sure what we liked. So they got us a little record player and our aunt and uncle bought us a small stack of random records. Their record choices were actually pretty good: The Beatles' Second Album, The Beetle Beat by The Buggs, More of the Monkees, Jimmy Soul and the Belmonts, Tom Jones's It's Not Unusual, and that Batman record, which was our first exposure to Sun Ra but we didn't know that back then. We got these around 1969 and we played the shit out of them.

The Beatles were the first band that made me want to play the guitar so we can lay the blame fully on them. I didn't start playing guitar seriously until I was 16. I had a couple of good friends who could play quite well. They were patient with me and they showed me a few basics and some chord progressions, mostly so I could play rhythm and they could play solos. That was really all the external guitar training I had. I just learned on my own after that. I wasn't interested in being properly taught how to play or to learn music theory or any of that. I didn't have the patience or the discipline. I was lucky because once I knew a few chords I could figure a lot of things out by ear. I began listening to the entire crop of classic fret-wankers, old and new. Hendrix of course was on heavy rotation when I first started playing. But there was also Ritchie Blackmore, Jimmy Page, Pete Townshend, Steve Howe, Carlos Santana—hey, how about Jeff Skunk Baxter? There was also Glen Buxton and Michael Bruce from Vic Furnier's little outfit. And there were so many others. I just listened to all of them and copped what I could. We all start out as imitators. But a lot of these guitarists eventually reached a plateau with their playing and kind of got stuck there so I abandoned them. Then Eddie Van Halen broke onto the scene with that first record that came out in 1978. It was pretty crazy stuff. Most electric guitar players loved it. I did too, for about 20 minutes. But then everybody wanted to sound and play just like that and within a few months there were hundreds of one-trick ponies out there, grazing away in a huge field of somebody else's shit. And that concept has multiplied into unlimited genres. That's just how it is.

I never was much of a Blues man. I liked some of the early players from the 1920s up through the Hubert Sumlin administration. The more uneven and erratic they played the better, but other than that not many straight-up Blues guitarists have ever done anything for me. It all sounds the same to me. It's guitar in a can. And there's so many out there. I could give you a long list of legendary blues guitarists whose work I can't stand but it's hardly worth bringing up their names. Besides, it would just piss the die-hards off, and even though that brings me great joy, it should be noted that I'm not implying that these particular fucks don't know how to play guitar. I'm just saying that they were never playing anything new or remotely interesting—it's the same old tired shit. That form of Blues playing is long dead—it went out with wooden airplanes. If one is going to play Blues guitar nowadays, they better reinvent the damn form into an unrecognizable state, and there better be some pain involved.

When it comes to Country music I wasn't really exposed to it that much, but my dad was never one to miss an episode of Hee Haw and I do remember watching Roy Clark tear it up with a flashy instrumental every now and then. The only other country player that I really knew about was Chet Atkins, and after listening to him you really don't have to go any further. He was the best in the business.

In 1979 I got hold of a 10-inch record by Les Paul called The New Sound, and around that same time I first heard Django Reinhardt. These two changed everything. I tracked down as many recordings as I could by both of them and dove in. I tried to figure out how they were doing what they were doing, and I failed miserably. But they left their mark. They both sounded so different from the heavy rock sound I was used to. I started listening more to Jazz guitarists like Barney Kessel, Wes Montgomery, John McLaughlin, and Al Dimeola. Then I heard Robert Fripp and James Blood Ulmer and some others who gave me even more ideas to think about. At that point, I had to stop and re-evaluate things. I noticed that I was just trying to imitate these guys and I wasn't really being very creative. So I decided to try and come up with my own way of playing, and to establish an approach that would result in a unique style or "sound," one I could call my own. That was thirty years ago and I'm still not there but, regardless, that was when I began to improvise and started playing in a different way. I began playing stuff that didn't make sense. It wasn't very popular with my guitar-playing friends but it was a huge turning point for me. It was making me think differently about the guitar. It was around then that I "remembered" the music that my grandfather was playing back in Michigan and I began experimenting with Eastern sounds. I started listening to oud players as well as Indian masters of sitar and sarod. But I didn't copy anything, I interpreted the "feeling" of the music instead. Then Sun City Girls formed and I was able to continue trying new things with the guitar but now within the framework of a working band, with two other people who also had their own unique "take" on how to approach their instruments.

Along the way I did listen to some Flamenco players. There was Carlos Montoya and Paco De Lucia and several others whose names I don't recall, or never knew to begin with. I was always more affected by the energy, and the rhythmic patterns of the style, than by the particular notes that were being played. I never really listened much to African guitarists. I wasn't really tuned into them at all. Recently there has been Group Doueh, Group Inerane, and others from the Sublime Frequencies records and films. I like the rawness of the sound and the desert rhythms but it's not anything that will greatly affect my own playing. I'm trying to move in other directions.

As far as my own releases are concerned, I don't use any specific formula as to what they're going to sound or end up like. I usually don't know until the studio session is over. The Freak of Araby is a perfect example. The whole thing was an accident, though a fortunate one. I never planned on doing a Middle Eastern record. I had a whole bunch of original song ideas that I was going to develop in the studio, two of which were based on Middle Eastern themes. I did plan to record one Omar Khorshid song that Sun City Girls had performed live on a few occasions. This was the only "cover" song that was intended for the record. But after listening back to the six rough tracks from the first day, the three Arabic pieces stood apart from the others; I decided right then that I wanted to have the entire record reflect this type of sound. So I scrapped the other songs and went home and dug out my Khorshid recordings and learned a few overnight and just went back in and went for it. I made up a few more original songs in the studio and after three days I had enough for a full record. Considering the little time I had to prepare for it, I think it turned out all right. Khorshid's work definitely inspired much of the scattered process but it was more of a spontaneous celebration than anything else.

Within the past few years I've stopped actively listening to guitar players, with the exception of Django. I'm more likely to be listening to Coltrane, Captain Beefheart, the Beatles, Sun Ra, or Tom Waits. These are my go-to guys—the ones that have earned my loyalty and who inspire me the most, perhaps not as a guitarist but more as a listener and a performer in general. I'm constantly exploring their entire bodies of work and I never tire of it. Don't get me wrong, there are great guitarists out there that I love to listen to if I get the chance: Nels Cline, Mark Ribot, Bill Orcutt, and others. They're great players. I just don't actively seek them out. But I'll always have my ears open for those who are attempting to take their playing (and the instrument itself) into new territory; playing things that nobody has heard; innovators, risk-takers, and of course those who don't give a fuck about what others think.

J. Kaw

When composing music, do you still make use of the unique approach to notation you mentioned in the 1999 interview? You have noted in interviews for Arthur and Foxy Digitalis that your solo performances, both live and in the studio, consist of a significant amount of improvisation, but that particular songs, after a certain point, cease to impel further exploration—that you're "finished" and "done with them." Have you found a way around this problem, besides introducing new songs? How would you describe the impetus behind improvisation in your solo career? Practical? Pleasurable? Or perhaps connected to certain assumptions and opinions about the inherent value of musical improvisation?

Richard Bishop

That approach you refer to isn't really a form of notation because nothing ever has to be written down. It's just one of the exploratory tools that I came up with when I was trying to formulate my own system in the early '80s. I can use it at any time. It's just playing with (and within) certain shapes on the fingerboard: geometrical, linear, or otherwise; and utilizing various patterns (diagonal, circular) for chord forms and single notes among the different strings without relying on any predetermined chords or any particular mode or scale (I don't know shit about scales).

Working with this and other improvisational approaches forces me out of any comfort zones and gives me access to unfamiliar sound patterns. It always yields results. I like to improvise—it occupies most of my time. In fact, I'm improvising right now. For me it's a huge part of the compositional process. I've never been able to sit down with my guitar and say "okay, I'm going to write a song now." It has to just happen on its own. Practically all of my solo recorded works either began as improvisations, or were total improvisations. The pieces often start with a phrase or a series of phrases or chord forms that I stumble upon, usually by accident, and by exploring the areas around those forms the songs build themselves over time. At first there is a lot of room to work with within each piece but on some numbers those empty spaces start to fill up with ideas that stick, so eventually the song doesn't require anything more. You have to know when to stop. And at that point you just move on to a new set of bones and start to add flesh again. The cycle renews itself. But when performing live almost anything can happen. I can choose songs from my records and interpret them differently, or stretch them out in order to create new spaces to work with, or I can just play them the same way every time if I want to but that gets old after a while. The trick is to keep things interesting enough to hold people's attention. Sometimes it even works. Even when it doesn't work as you hoped it would, it can still lead to some unfamiliar places and that's a good thing. I enjoy improvising, and even if I get lost doing it, I'd be totally lost without it. It's a sticky subject. It has the power to appeal to people or to repulse them. I'm happy to go either way with it. And there are different types of improvisation. In a straight-up Jazz combo it might only be the soloist who is improvising while the rest of the band is not—but is it true improvisation or is the soloist just riffing on a scale that his music theory class told him would work with whatever chord progression is being played? Hey, it's a valid question. When you get into the area of Free Jazz there may be no tonal center at all so the entire band might be going completely nuts with the improv. So it can be limited or unlimited, controlled or uncontrolled. It's hard to define it or pin it down. It's alive! ALIVE!

Improvising as a solo performer is the most challenging because nobody has your back. You're all alone and there's nothing to work off of. So to me, in it's purest form, improvisation is the fine art of making it up as you go along without thinking, always finding yourself in that moment of Creation. You jump in and immediately begin struggling, not knowing what the next note or chord is going to be and immediately forgetting what the previous ones were. No dependence on scales or theoretical formulas—it's walking the tightrope without a safety net to catch you when you fall, and believe me, falling is half the fun. One plays by feeling, by gut instinct. It happens. It just is. This type of improvisation can be very frustrating to an audience (if you do it right). It all depends on what comes out of your instrument. You're always aware that things could go terribly wrong. This is where confidence and fearlessness get tested to the fullest. And it's always one fuck of a ride!

Visvanath temple, Khajuraho, Madhya Pradesh, India

J. Kaw

The recent reissue of the eponymous first album Alan released under the moniker, Alvarius B, has reminded us of the curious fact that he released a solo-guitar collection in 1994, four years prior to the release of Salvador Kali. How would you describe the differences between Alan's style and methods on the guitar and your own? How have you directly effected each other's playing techniques, beyond the obvious factor of playing together for what amounts to a significant portion of your lives?

Richard Bishop

I imagine many would have expected me to release a solo record before Alan but he was way ahead of me. But, hey, hundreds of people released a solo guitar album before I did. I knew that I would eventually put something out—I just wasn't very active about it. I was thrilled when Revenant asked me if I wanted to do one. That was my chance so I naturally jumped on it, and having it be on Fahey's label didn't hurt anything. But there has never been any competition with Alan about releases or who does what first. Our guitar styles are quite different but I've always liked his particular approach, which is one that he developed on his own over the years, much like I did. He uses a lot of unique rhythmic patterns that on first listen sound like they are African-based but I'm not entirely sure of the source. He could easily have come up with them on his own. During our recent (Brothers Unconnected) European tour he would tear into some of these rhythms and it always took me a second or two to figure out what to play against it. He has his own unique picking pattern as well. He just starts grinding away at the strings and the picks disintegrate over time but it creates a really cool percussive element that adds a lot to what he's playing. My playing is perhaps more linear and I may try to play a little cleaner than he does but when we play together our individual styles compliment each other in a great way.

Up until just recently he always played this old Yamaha acoustic which was his first guitar—he got it in the late '70s. Somewhere along the way the guitar developed a particular string buzz that used to drive me completely crazy. You can hear it on all of his solo records and on many Sun City Girls songs. At our recording sessions I would always try to convince him to play a different guitar in order to avoid that buzz; it became a running joke and a totally hopeless pursuit. It took me a while but I've finally come to appreciate it—it's become part of his signature sound. I would like to also mention that Alan is a professional string breaker; in fact, nobody does it better. During the first Brothers Unconnected tour he would break a string every night—sometimes two strings. It happened so often that we had no choice but to incorporate the "string breaking" segment into the show. It was written on the set list. But he is quite adept at playing the guitar with just five strings and can still get it to sound just fine. Besides, that extra string can get in the way sometimes—just ask Keith Richards.

I've borrowed a few things from Alan's playing over the years, mostly in relation to the polyrhythmic patterns he uses. He has always had a "fuck all" approach to playing which goes back years, and though I have a similar approach he takes it to a whole other level. I don't know if my playing has influenced his—probably to some degree, but you'd have to ask him in order to get to the bottom of it. Neither of us have had guitar teachers or any proper musical training. We've learned it on the battlefield and have both developed our own way of doing things. That's really the best way to do it in my opinion, though millions of trained seals will tell you otherwise. I mostly consider Alan as an acoustic guitar player but there are many instances in the past where he has strapped on the electric and just let if fly. What a lot of people might not know is that he has played a fair amount of electric guitar on Sun City Girls records. A recent example is on the song "Ben's Radio," which is the first track on Funeral Mariachi. All of that chicken-scratch and squawky, rhythmic reverb-drenched electric guitar before the noisy freak-out section is played by him. And it's great. There were a few Sun City Girls shows back in the '80s where we both played electric guitars and there was no bass. The same happened with some studio material as well, primarily around the Torch of the Mystics sessions. There was a great moment when Sun City Girls played Seattle's Bumbershoot festival at the Experimental Music Project back in 2004. We just brought a bunch of shit to the show: costumes, props, and random instruments. We did bring an electric guitar but I had no intention of playing it for this show—I was mostly playing keyboards and shortwave radio and dancing like Carmen Miranda with fruit on my head. But the guitar was up there (next to the dancing Saddam Hussein doll) and in the middle of the set Alan, with his Osama Bin Laden t-shirt on, just picked up the guitar and without thinking began wailing on it. I'm not sure if it was even in tune, but it didn't matter—it killed! It reminded me of some of Glenn Branca's wilder moments. I didn't even realize it had happened until I watched the video of the show long afterward. It only lasted two minutes or so but that was all that was needed. And his bass playing is phenomenal as well. I've never heard anyone play it like he does. He never had any training on that either and that probably has a lot to do with it.

Phin player, Vientiane, Laos, 2009

J. Kaw

In his Correspondence, Alan claimed, "there is no Sun City Girls logo" or image, reaffirming a definite refusal to allow others to delineate too strictly the nature and meaning of Sun City Girls. At some point in the years hence, I considered maybe a contradiction existed between this refusal to set Sun City Girls in a certain context or artistic category, on one hand, and Sublime Frequencies making use of common national, ethnic, and cultural distinctions. The albums the label has released refer to Burma, Pakistan, Vietnam, Palestine, China, Iraq, Singapore, Algeria, Thailand, Syria, Laos, Niger, India, Morocco, Cambodia, and Nepal, in addition to various cities, regions, and formal administrative divisions. Moreover, common genre distinctions, such as Molam and Jaipongan, are used. Especially as you're not as regularly involved in Sublime Frequencies as Alan and others, perhaps we should consider how these problems manifest themselves more broadly: in traveling to foreign lands, newly appreciating certain cultural practices, attempting to drop pretenses and hidebound beliefs characteristic of one's "homeland." You've talked about these kinds of adventures, especially in India, and the difficulty you've faced as an outsider looking in.

Richard Bishop

The world is full of contradictions but one reason that Sublime Frequencies can use such distinctions is because they already exist. There is a filing system in place, a historical tradition or series of traditions (cultural, musical, or otherwise) that can be worked with—one just has to figure out what goes where but only if one chooses to do so. If you look at individual performers or groups from some of those Sublime Frequencies releases, they may only fit into one category or style of music within the musical tradition of their particular country or region. It's almost expected that they be categorized (at least by academics) or placed in a file of sorts as a frame of reference, so that others may understand. But again, it depends on whether one chooses to do this or not.

It's just not that cut and dry with Sun City Girls. As Alan hinted at, when it comes to the majority of bands in the Western world, you can usually figure them out pretty quickly, label them, throw them into a simple filing system and then be done with it. There's nothing wrong with that. It's just how it is. But when it comes to Sun City Girls, it's not as easy to simplify it like that. There aren't enough cabinets. I'm not sure which national, ethnic, or cultural distinctions would apply—perhaps none of the above. The material is all over the place. You'd have to file things away in small chunks. You would almost have to go song by song, and probably have to listen to each song more than once in order to file it away properly. It can't be done with the group as a whole or even by album. It doesn't mean Sun City Girls were better or worse than any other band. We just operated a little differently and took on more than most. People will have to expend a little more energy in order to pigeonhole us in any meaningful way.

In regards to traveling, any problems or difficulties I may have had in the past while visiting other countries are just steps I had to go through in order to be better equipped on future trips. It's something that each person has to deal with individually and can't be blamed on others or the way certain cultures do things or don't do things that one would expect them to do. These are not really problems, just little doses of reality. I still expect things to be different elsewhere. It's one of the main reasons I go in the first place. But on recent trips to Southeast Asia and India, I've noticed that, at least in the major cities, things are becoming more and more like they are in the West. I understand the reasoning behind it. Everybody wants a better life and a lot of people in underdeveloped countries have struggled more than others. Who am I to try to hinder that in any way? I may not agree with what some may consider as progress but there's nothing I can do about it. It's not for me to decide. During a recent visit to Calcutta I noticed more and more people carrying cell phones and looking at them as they walk down the street, not paying attention to anything, just like everywhere else, whereas on previous visits that just wasn't the case. As long as they watch out for the open manholes they'll be fine. In Thailand and Laos, everybody seems to be sending texts while they're driving their scooters. It's easier to count the ones who aren't doing it. So they have caught up with the West in many ways that I wouldn't have guessed a few years earlier. But again, that's just how it is and there's no stopping it. So I just adapt to the changes as needed.

Traveling in Asia becomes easier for me with each visit. I don't really have any specific expectations going in because they get shot down immediately, especially in a place like India. You have to take what it deals you and then work from there. I still have the habit of being totally aware of what's going on around me whenever I am walking down a road, but that just becomes automatic after having to endlessly deal with hustlers on previous visits. The hustlers are still there, trying to separate you from your money and their tactics have improved over time but I know how to handle them much better than I did on my earliest visits. It's now quite enjoyable. Humor is the key. Once they realize that you know the game, everyone can relax, and even enjoy each other's company. And once they know where you're from they want to talk about things specific to the U. S., whereas I would prefer to pick their brains about their country. So you just find the right balance and then it works out. It is still common to be viewed as an outsider by the local people in rural areas. It's a natural reaction, but I don't view myself as an outsider while I am there because that doesn't help me. I try to embrace things from a direct experiential viewpoint in order to grasp everything in a way that will be beneficial for all involved. I don't project any particular nationalism on anybody—I never have. It doesn't matter where I'm from. It only matters where I am.

J. Kaw

The addition of "Sir" to your stage name as a solo artist—which strikes me as a humorous evocation of the notion of the British empire as world leader and benefactor of its subjects—seems to acknowledge these cross-cultural, cross-ethnic tensions. The veneer of gentleman imperialists as servants of the greater common good, and enablers of Whiggish hopes for human progress, of course masked a great deal of violent force, murder, lawlessness, and venality, inherent in any sort of imposition of governmental control perceived by its targets as foreign. The knightly persona of Sir Richard Bishop serves as a quick witty retort to the listener's search for exoticism—my own question about your grandfather's influence, for example.

Richard Bishop

For many years a few friends of mine called me Sir, some even called me Sir Richard. So it just seemed like a good fit—had a nice ring to it, and there was the connection to another Sir Richard who we'll get into in a minute. I like the honorary title and, after all, I do think highly of myself, so why not? A Knight—how chivalrous! It was obvious that I could never get this title by any normal means—it would never be given to me by a member of some ancient money-soaked family who insisted that their blood was blue (we should cut one of them open and settle that debate for good). But it should be known that I have at least made every effort possible to make this knighthood official. During my many visits to the Greater City of London I have traipsed the hallowed corridors of Buckingham Palace, the Ministry of Finance, Freemason's Hall on Queen Street, the Natural History Museum, and even the Reptile and Amphibian House at the London Zoo, just trying to meet someone who knows Liz personally, and who could perhaps pull a few strings in order to get me an appointment with the old dragon so that I could get it finalized once and for all. Every time I leave a phone message she never returns my calls (David Icke usually calls back within minutes). I imagine she is just too busy counting her money and fondling the crown jewels, watching old Benny Hill reruns, or practicing her reptilian transformations in front of her magic mirror—the one she keeps underneath the chamber pot on her throne. She has a fucking throne! My sources have told me that she actually has an attendant that wipes her ass for her, and once that little relationship gets established you just become lazy. That's totally understandable. But I'm evidently not a worthy subject, just a lowlife in her proud basilisk eyes. Next time I visit I think I'm going to try to work directly with the Prince of Wales—you know, Tom Jones. That wouldn't be so unusual.

After all this frustration I decided to conduct my own official ceremony. I forged a sword from the finest steel I could find: from the hood of a 1966 Buick Wildcat. Once I pounded it into the shape of what looked like it could be a sword, I let it cool and then fashioned a handle made out of gold (but actually filled with tungsten—it was all I could find) and wrapped it in a swatch of elephant skin. I've got the rest of the elephant right here in my pocket—would you like to see it? I studied the ritual, learned a few words in Latin, and proceeded to knight myself with honors, in a makeshift chapel (tool shed) in Milledgeville, Tennessee, just down the road from Carl Perkins' house and about five miles from Jacks Creek. And now, I no longer have that not-so-fresh feeling.

Kali shrine, Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India

Then there is the other S. R. B., the quintessential "Sir Richard," that being Sir Richard Burton, the great author, explorer, and cunning linguist. He has been an inspiration to me ever since I read portions of his translation of the Arabian Nights. He got extra points because he didn't censor anything like the other translators did. Quite the traveler Burton was—disguising himself as a Muslim and entering Mecca, his death-defying adventures in darkest Africa and elsewhere. He had balls the size of coconuts. He mastered dozens of languages. His literary output was mind-boggling to say the least—it's amazing he had time for a fraction of it. He lived a thousand lives in one life. And being a Royal Servant of the British Empire, working for crown and country, I'm sure he had specific objectives while traveling: the gathering of strategic information, perhaps determining what resources were available and how to procure them—who knows? He made up for it with his literary output so at least he brought the goods! He eventually rebelled against the system anyway. He was certainly no angel, but who would want that? So yes, the whole idea of the gentleman conquerors and their selfish pursuits for land and whatever resources they were seeking has always been a history of tragedy, but a fascinating study just the same. A huge military force disguised as simple traders in tea, silk, opium, and whatever else, always with an air of good intentions. From the East India Company to the Raj, the players of the Great Game, and everything in between, and of course it wasn't just the British but, regardless, it is quite a lesson in conquest, domination, espionage, and intrigue, not to mention rape, pillage, and murder. It's how Empires are built, how diseases are spread and how brown people die. It continues to this day. The players have new faces, oil has replaced tea and silk, opium is still on the frontline, and the control of food, fresh water, and oxygen is the final goal (we're fucked). Everything else remains the same, including the welcoming notion of "hey, we're here to help" or "it's for your own good," though now they call it "democracy—as we like to see it" or my favorite: a "humanitarian mission."

J. Kaw

After early tours as a headlining act, including in 2005 when Akron/ Family opened for you, Sir Richard Bishop increasingly developed a niche as an exemplary opening act, touring with Animal Collective, Bonnie "Prince" Billy, Bill Callahan, and Earth, among others. In contrast to the common, often very boring, model of the opening bands being too similar to the headliner, or imposed by record labels or promoters, your solo performances are marked by a level of coherence and musicianship probably not matched by the headliners; but at the same time, being briefer and requiring closer attention, they wouldn't work as a main act in a nightclub setting. In the last two years, though, you've returned to performing with bands: an ensemble supporting The Freak of Araby in 2009 and Rangda, with Ben Chasny and Chris Corsano, in 2010. Generally speaking, you've toured as a solo artist more frequently than with Sun City Girls. Having experienced a variety of music scenes and social settings, from the "skate Punk" of the early-1980's Phoenix to the West-coast "isolationism" of like-minded artists Caroliner and Climax Golden Twins, as well as being able to draw upon travels abroad and the resulting interaction with foreign musicians, one can't help but wonder what observations you've made about the current state of Indie music (for lack of a better non-anachronistic term) or of contemporary U S and European culture. When Sun City Girls opened for Thinking Fellers Union Local 282 for a national tour in 1992, the market for "alternative" music was growing dramatically, but in many aspects such artists might have felt more alone in what they were making and promoting. Moreover, most of the cities that had experienced significant depopulation, economic decline, and rising crime from the 1950's onward had not gone through the rapid gentrification of the late-1990's boom. Nevermind for the moment the abysmal effect gentrification has had in some cases; it has certainly led to more crowds, more venues, and more artists.

Richard Bishop

Let's see, the current state of "indie" music—how about comatose? I guess I could just go to Pitchfork and find out what all the kids are masturbating to this week. I really don't keep up with that scene even though I get lumped into it every now and then. Anything that I may have heard by chance or by accident over the last many years has just sounded rather banal and there really isn't anything challenging happening, at least not to me. If somebody described their band to me and said they played indie music I would probably just walk away. They should know better. I consider it a derogatory term, one that was created by someone in the music "business"—you know, one of those people that cares about everything in relation to music, except the actual music. What does it mean—independent? Of what—talent? It doesn't explain anything about the music itself. So when I hear that phrase "indie rock" I just think of any number of bands or artists that have no inclination to do anything unique or different from what has come before. And in that respect, they're actually in the mainstream. So congratulations are in order—they've made it to the top of the rubbish heap. To me that descriptive phrase means that there is nothing special about their music. And they number in the millions. But that's the problem, there are way too many bands and most of them just get lost in the muck. I'm sure there are some good ones out there. I just don't hear them. Sun City Girls were lucky to have started back in the early '80s when the Punk scene was going strong. There were less bands compared to today but still the amount of three-chord Punk bands back then was staggering and the majority of them sounded and acted exactly the same. It never really did anything for me. The whole Punk scene, regardless of its cultural influence and (some would say) importance, was just dull as dirt to me. Sun City Girls and a handful of other bands that were a little more daring were still absorbed into that scene, but were different enough to be able to exist outside of it simultaneously. And that seems to be the important point when one is talking about almost any genre since then. Take the Metal scene (please, just take it away)—whether it is Speed Metal, Death Metal, Thrash Metal, Black Metal, or whatever descriptive term you want to put in front of the word—it still all sounds the same to me and I can't tell one from the other because very few are taking it anywhere new. I just refer to it all as white metal. Grunge and early '90s Rock, the same thing applies—a few snuck through and stood out and the rest went on as impostors. Rap and Hip Hop, same thing. Add modern pop, Country, certainly Blues, freak Folk, white Jazz, and whatever else you want to call any type of music that is out there today—nothing is different. Which brings us full circle back to today's wannabe indie superstars. One has to be doing something really unique with their music in order to break out of the huge mass of mediocrity that is the current state of modern music. And very few seem to be doing it.

When I started playing solo I wasn't sure if I would like the whole idea of touring, especially since Sun City Girls only did a handful of tours in 25 years. My first solo tour was in 2005 and it included a trip to Australia to be a part of the "What is Music" Festival. I really didn't know what to expect, I just wanted to play. But I had a chance to perform alongside The Dead C, Sunn O))), Pan Sonic, and many others. The Residents also played the festival. So there was a lot of variety and I got to perform in front of a lot of people who had never heard of me or Sun City Girls. And I just had an acoustic guitar when most of the other acts were electric or electronic, and very loud. You don't really know what the reaction is going to be like when you are in that position, but I live for those moments. I just want to play in front of as many people as possible and I don't care who they are. In order for me to do that it is best if I remain an opening act for bigger artists. I have headlined shows every now and then, including that tour with Akron/ Family and the Freak of Araby tour but it's always been a crapshoot. Those headlining shows were usually in smaller venues or rooms, and I do sound better in a small room where the audience is close and the mood is a little more intimate than, say, a large theater. But you get more exposure in the big rooms. I remember the first show of a tour I did with Will Oldham in Europe. It was at this newfangled theater in the Netherlands and when it was time to follow the Spinal Tap maze from the dressing room to the stage, I walked out and there were 1,500 people sitting quietly in their seats. The seats rose into the sky; you could look straight up and there were people up there looking down, way down, at a speck on a stage. It makes you feel quite small. But as soon a I hit that first note or chord it's like there's nobody else in the room. I just do my thing as if I was at home sitting on the couch. When the show was over the applause was deafening. That's a good feeling. And that's usually been the case when opening for bigger acts like Devendra Banhart, Os Mutantes, and most recently, Swans—all of which were audiences that really didn't know much about me. I've been quite lucky. It's always better if the opening act's music is not the same as the headliner. It's overkill otherwise. But I wouldn't necessarily agree that my "musicianship" is not matched by the headlining acts I've worked with, it's just a different thing.

I love to tour and I'm always looking forward to the next one. I have no intention of stopping. It's frustrating because I don't know what to do when I'm not touring. I need to be on the move, like a shark. It's what keeps me going, and it pays my fucking rent. I will always consider live music to be more interesting than recorded music, whether it's mine or someone else's. That's where the action is; there are always factors involved that come into play where great things can happen or things can go terribly wrong. It's real life. In the studio you can make anything sound perfect and be done with it. That's totally fine but within a live setting there are always more energies to work with or to have work against you. It's way more adventurous for performer and listener alike. And while I have mainly toured as a solo act, I have enjoyed the recent group activity from the last couple of years. The Freak of Araby tour was somewhat of a new experience for me, even though I played with Sun City Girls for over 25 years before that. I had to assemble a group of players that I had never worked with and it was a pretty tight-knit affair since all of the songs were complete and there wasn't much room for improvisation. We had to rehearse a lot before the tour began. I wasn't used to that. I had to be a dictator to a certain degree and that made me a little uncomfortable. It probably made them uncomfortable as well, but there was no other way to do it. They put up with my bullshit and they did a great job and that's the bottom line. With Rangda it's a little more familiar. There are a lot of open spaces to work with musically and Ben and Chris know the drill—we're all fucking road dogs, so we work together well. We've never rehearsed. We've developed our material in the trenches. We'll be recording a new record in February—this time we might practice—either way we'll be hitting the road shortly thereafter. I can't wait.

Sudder Steet, Calcutta, West Bengal, India

J. Kaw

Given that next year will mark five years since Charles Gocher's death, have you found yourself looking back upon the entire Sun City Girls experience, perhaps beginning to delineate the band's history? A major turning point seems to have come in 1993, by which time the band had entirely relocated from Phoenix to Seattle. In that year, the recording sessions for Juggernaut and Piasa...Devourer of Men took place, suggesting a broader array of tempos, styles, and textures that would be confirmed by later releases, not least 330,003 Crossdressers From Beyond the Rig Veda and Dante's Disneyland Inferno. Abduction Records put out its first releases, shifting the band from vinyl and cassettes to the digital realm. The band also purchased a gamelan. Quite a year! At risk of simplifying matters, I'd venture to say that Sun City Girls became less of a Rock band, less confined to the trio of guitar, bass guitar, and drum kit, giving proper due of course to prior instances when the band had certainly not confined itself as such, or later when the band did keep things so ostensibly simple (as on Djinn Funnel). Perhaps merely, in the early years, the cassettes and 45's, compared to the L. P.s, featured more of the outre recordings.

Richard Bishop

I think about the history of Sun City Girls quite often. It's taken up more than half of my life. There's a lot to process there, and putting things into any historical perspective is something I'll leave to others if anybody wants to take it on. Good luck with that. To me it was one continuous ride and the music was all over the place. We certainly never ran out of ideas. The cassettes contained a lot of material that no band in their right mind would have ever considered releasing. A lot of ground was covered on those cassettes, from the simplest of musical ideas to levels of insanity that are rarely reached these days. People just don't try hard enough anymore. But our first three L. P.'s [Sun City Girls, Grotto of Miracles, and Horse Cock Phepner] contained a lot of bizarre musical (and non-musical) moments as well. So the scope of the music may have changed from time to time over the years but never at the expense of anything we did prior. And there are still hundreds of hours of recorded material in the archives, a lot of which I haven't heard in years. I know for a fact that some of the most way-out stuff we've ever put to tape is still unheard, just crazy fucked-up sound experiments and skits and radio plays—all kinds of things from the early '80s all the way to the mid '90s. There's tons of it. The audio quality isn't that great on some of it but the levels of absurdity we reached are unsurpassed. Some of that material would make Horse Cock Phepner and Dante's Disneyland Inferno seem tame. Think about that for a second! Man, I have to dig that shit out.

I'm not sure if our approach to making music changed all that much after we moved to Seattle but there did seem to be a lot more activity with the band. We definitely did a lot more recording. Scott Colburn moved up there from Los Angeles and he, Alan, and Charlie got a house together. Just like that, there was a full studio at our disposal in the basement and we had all our equipment set up for the first time in a long while. It's hard not to take advantage of that. Prior to that we had worked with several engineers, almost a different one for each project, and to have Scott there all the time made things much easier. He worked on basically every release from the time we got to Seattle all the way until Funeral Mariachi. It also seems like we played more live shows once we got up there but I've never really checked the numbers on that one. As far as the music itself, sure, we ventured into some new areas but we were always doing that. Your reference to Juggernaut is correct because we had to think more in cinematic terms—matching sounds with visuals for the first time. So we approached it a little differently than previous releases. With Crossdressers and Dante's we upped the ante a little bit but I still feel that these two double discs were natural extensions of the first three Placebo records. The instrumentation changed a little because of the gamelan, and the piano was probably utilized more, but we always had a shitload of instruments at our disposal. It would have been great to use the gamelan at live shows more often but it was such a pain in the ass to haul around. Just getting it home from the auction where Alan got it took two trips each with a van and a station wagon. Damn thing takes up a lot of space. But even though I enjoyed using additional instruments whenever we could, when it came to live performances, I always felt we were at our best with one guitar, one bass, one drum kit, six arms, six legs, and three heads. That was really all we ever needed.

J. Kaw

To conclude, could you elaborate more on how you and Alan met Charles? The foundation of your friendship and collaboration with Charles bears reinquiry partially because Alan's piece in Perfect Sound Forever indirectly reminds us of Charles's influence on the literary themes of Sun City Girls, especially the topic of criminality; as if his prominent place on Dante's Disneyland Inferno and Sun City Girls films hadn't made it clear enough. You have noted too, in the Arthur interview, how Charles pushed your listening appreciation beyond Rock genres into Jazz. Could you describe who Charles, and who the Bishop brothers, were, before you all met—before Sun City Girls? Alan notes in his appreciation that Charles's unpublished notebooks extend back forty years. Was Charles working on his own music and film projects at the time as well?

Richard Bishop

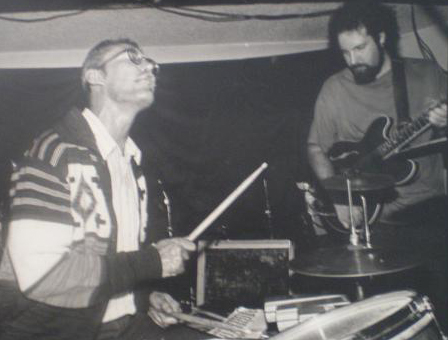

Let's go way back. Alan and I performed together on stage for the first time when we were about 12 years old. It was on our front porch in Saginaw in the form of a play, Tom Sawyer. My mom wrote up a script and we performed it for the neighborhood kids and their parents. About five kids made up the cast. I was Tom Sawyer and Alan was Nigger Jim. He performed in black face—and away we go. The only line I remember from the play was from Alan: "Aunt Polly take'n tar da head off a me, deed she would." Even then we improvised in order to make jokes about the parents in the crowd—we went way off script. And the rest is history.

We started playing music together when we were off at college. He was at Central Michigan University in Mount Pleasant and I was up the road at Ferris State College in Big Rapids. We would visit each other on weekends and play at parties or just on campus somewhere. We moved to Arizona right after that. We started playing regularly at the folky open-mic nights in Tempe doing cover songs. Then out of nowhere Alan started writing tons of great original songs. He just churned them out one after another. We were playing them acoustically. We knew that they would sound better if everything was electric. So Alan pulled a McCartney and took up the bass, I got a Fender Twin amp, we hooked up with a drummer named Stage Musico, we canned the cover songs, and we became The Next. We had a short lived cover band before that called Fuck You with a different drummer but that was destined to fail from the get-go. Through the open mic scene we had met Linda Cushma, who we would play with whenever we could. She had some cool original songs that were odd enough to set her apart from the normal performers, and she could play guitar, bass, and drums to boot. The three of us got along pretty good so we gradually incorporated her into The Next and soon thereafter we changed our name to Sun City Girls.

San Francisco, 1992

During all this Alan started running an open-mic night twice a week in the back lounge of a pizza joint in Tempe. That's where we eventually ran into Charlie. He washed dishes at the Dash Inn on Apache Boulevard, which was just down the road and he would blow in after work to drink and hang out. We didn't really know him yet nor had we ever seen him perform. That was about to change. An entire book could be written about those open-mic nights. It went from a happy, safe Folk-music environment to a weekly showcase of total artistic and musical terrorism in just a matter of weeks. The Next played once or twice, plus Alan started encouraging other friends from the fringe to come on down and do their thing: from performance artists to beat poets, Industrial and Punk groups, Free Jazz players, and a whole bunch of other unwelcome acts. The local clientele hated all of it. I remember one night somebody was on stage reading some weird, agitating poetry and the owners got pissed off and asked him to "go," so he decided to "go" by pissing on the stage—he was chased out the back door, he even had a getaway car waiting. I burned an American flag on stage one night—I don't remember why—maybe I just heard that it was illegal. It didn't go over too well. It was complete mayhem. It was at one of these nights when we saw Gocher perform solo for the first time. He was standing on a wicker chair with one foot in the air. There was a flashlight positioned underneath the chair that projected a patterned shadow against the back wall. He held a stick and was using it as a magic wand, waving it over the crowd. He had a tape recorder playing some Bebop instrumental and he was scat singing at the top of his lungs over the music with quite a rabid look on his face and his arms flailing about. The audience didn't know what to make of it. I didn't either but I was intrigued. So that night we hung out and talked shop. That's when we found out that he played drums, and after talking we realized that the three of us shared some common interests including a non-traditional approach to making music, not to mention a general disdain for most of humanity. So we started doing this thing at the open-mics called the Freeform Orchestra, which was the three of us and whoever else wanted to sit in. The only rule was that everything had to be totally improvised.

Things gradually began to change. My guitar playing was getting way more experimental, into the land of "who the fuck cares," and Alan and I were starting to move away from typical song structures. Our drummer Stage got frustrated with the direction we were heading in and he didn't like the idea of having a girl in the band anyway so he decided to quit. After Stage split we played a few Sunday nights with Cushma at this place in Tempe called Friar Tucks. After one particular show a guy named Jesse Srgoncik asked us what we were called and we told him Sun City Girls, even though I don't think we planned on keeping that name. He ended up writing an article about the Phoenix music scene that got picked up by some L A paper and his article mentioned Sun City Girls in a positive way so the name stuck. Jesse, Alan, and a guitar player named Benny Baresi hooked up with Moe Tucker and started the band Paris 1942. I used to go and sit in on some of the practices at Moe's house and eventually they kicked Benny out of the band and I replaced him. I only remember doing three live shows with Paris 1942 (Phoenix, Tucson, and Los Angeles). We met Nico after the L. A> show. She played the same night as we did. We were staying at the Tropicana Hotel and she came over afterward to see Moe for the first time since the V. U. days. But Paris 1942 didn't last long. Moe and her husband divorced and she left town in a hurry with the kids. It was really too bad because she was so nice and easy to get along with. Jesse and Alan had also worked with David Oliphant in a group called Destruction, which was noisy, dark, highly experimental. Oliphant also worked with and recorded Sun City Girls from time to time (Square 9) but his main group at the time was called Maybe Mental; Alan was a member of that for awhile. Jesse, who also went by the name of J Akkari, would eventually join Sun City Girls onstage for a few shows and was on some early recordings that ended up on one or two of the cassettes we put out. He had a unique approach to guitar playing which didn't go unnoticed. I learned a lot from him in that short time. He also turned me onto Captain Beefheart.

Charlie became a permanent member of Sun City Girls shortly after Paris 1942 fizzled. Cushma was still in the band as well. The third show we did as a quartet was at a house party. It was Charlie's 30th birthday. During the set, Linda left the stage for a while and became a spectator while me, Al, and Charlie played for several minutes. While we were playing she turned to Tony Victor (Placebo Records), pointed to the stage, and said, "that is Sun City Girls." She officially quit the band in the car on the way home from the gig. A few weeks later we did our first show as a trio with Gocher, opening for Black Flag.